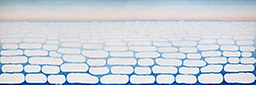

If I had to pick a favorite painting, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Sky above Clouds IV would be it. Most if us know O’Keeffe from her flowers, cow skulls, or austere landscapes. Any one of her paintings would top my list, but this one is magnificent.

When O’Keeffe began to fly in the 1950s, she started a series of works responding to what she saw from the air. The Sky Above Clouds series started with a small, relatively realistic version of puffy white clouds. She gradually abstracted the images on larger and larger canvases, culminating in this one. Here’s what she wrote:

“I painted a painting eight feet high and twenty-four feet wide—it kept me working every minute from six a.m. till eight or nine at night as I had to be finished before it was cold—I worked in the garage and it had no heat—Such a size is of course ridiculous but I had it in my head as something I wanted to do for a couple of years so I finally got at it and had a fine time—and there it is—Not my best and not my worst.”

Sky Above Clouds IV fills an enormous wall at the top of a grand staircase in The Art Institute of Chicago. It slowly comes into view as you climb the stairs. The only painting in sight, its expanse and simplicity will take your breath away.

O’Keeffe was seventy-seven years old when she made this painting. As she aged, she clearly wasn’t afraid to explore new motifs, to expand in size, and to push towards even more abstraction. As an artist of a “certain age” myself, this inspires me. Her age also tells me something about the images of clouds and the title of the painting. O’Keeffe is not looking down but looking up. The clouds themselves are merely a basis from which to move to the next level of existence, whatever you may imagine that to be.

As another year has passed, I can feel changes in my own perspective. I am losing interest in many things that had been a part of me. I don’t cook extravagantly. I wear the same clothes over and over again, particularly when I paint. Smaller pleasures are more meaningful: a glass of wine with my husband, playing ball with the dog, enjoying an early morning walk outside. The need to be with people all the time, playing with language, has been replaced by the joy of being alone in the studio, interacting with paint, brush, canvas.

Physical change as well as perspective change is taking place. I have had to make peace with a different way of staying fit. No more extreme sports. It’s nice, actually, to smooth out the rough edges of needing to be on the mountain or on the river. I am letting go of the addiction, which it was, to physical risk.

The risks now are in my artwork. After decades of painting, I may be finding a new visual voice. I’m getting comfortable breaking rules and having the courage to say, “This is me. This is how I want to paint.” I’m letting the “errors” be the strength of my expression. My nascent new standard: “Do I want to look at this?” Not, “Is it correct?”

O’Keeffe painted her last unassisted work when she was eighty-five. Even when she was almost blind from macular degeneration, she continued to create with the help of assistants. At ninety, she said, “I can see what I want to paint. The thing that makes you want to create is still there.”

Onward. We will all face the physical and mental shifts of aging. I’m choosing to experience them as blessings. The world may get a little more circumscribed, but the will to make art can explode within that smaller circle.